The British musician on a mission to save the country's unwanted pianos

Tim Vincent-Smith repairs the discarded instruments, offering some for adoption and turning others into art

In a deserted former department store near Edinburgh, Scotland, Tim Vincent-Smith reaches inside a grand piano's open top, his fingertips lightly plucking at the taut strings.

The piano is one of hundreds rescued by the musician and his team of volunteers, as homes around Britain discard the instruments in favour of more space.

Vincent-Smith's aim is to refurbish as many pianos as possible before putting them up for “adoption”. Those beyond repair are turned into art or furniture.

A customer tries a piano at the Pianodrome, a centre aiming to refurbish and repair pianos in Edinburgh, Scotland. Photo: AFP

“I discovered that there were loads of pianos going to the dump and so I started making furniture – a window seat and a kind of high bed with a staircase – and then the pianos just kept on coming,” he told AFP.

As the instruments flooded in, Vincent-Smith realised that many were still “pretty good”, and so he and his bandmate Matthew Wright decided to set up Pianodrome, to rescue as many of the instruments as possible.

“If you are lucky, you may find a beautiful antique piano which has a good action and tone, holds its tuning and is a pleasure to play,” he said.

“The best thing for an old piano is to find a new home.”

Britain's piano-making tradition

Piano keyboards pictured at the Pianoodrome, a centre in Scotland where the instruments are refurbished and repaired. Photo: AFP

Britain has a piano-making tradition dating back more than 200 years, boasting some 360 manufacturers at its peak in the beginning of the last century.

The country was a supplier to the world, including to great Western classical composers such as Frederic Chopin, Franz Liszt and Johann Christian Bach – the youngest son of Johann Sebastian Bach.

Pianos were once central to British social life and identity, taking pride of place in homes and local pubs, where they were used for rousing singalongs.

But as homes shrank in size and stairways grew narrower, it became increasingly difficult to shift pianos in these spaces.

Television and later electronic keyboards began providing an alternative source of nightly entertainment, leaving traditional pianos to gather dust in the corner of living rooms.

Homeowners even started finding innovative, if destructive, ways to get rid of the instruments – in the 1950s and 1960s, competitions were held to smash pianos to pieces with sledgehammers.

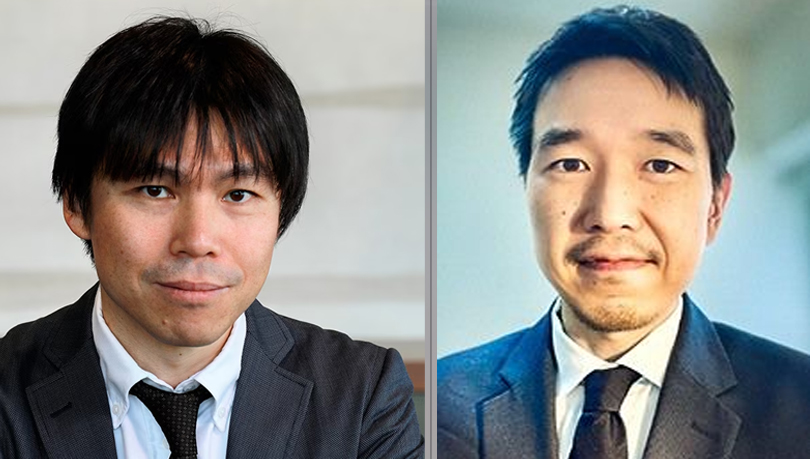

Matt Wright and Tim Vincent-Smith pose with one of their upcycled sculptures made from abandoned pianos. Photo: Getty

Vincent-Smith first came across dumped pianos when he started building furniture 20 years ago. At the time he was living and working at the Shakespeare and Co. bookshop on the banks of the River Seine in Paris, now a popular tourist attraction.

The owner would send him to local skips to collect wooden planks for making shelves, benches and beds for the itinerant staff who worked in the shop beloved of writers such as Ernest Hemingway.

Vincent-Smith said he was often stunned at the quality of the pianos that were being dumped around the French capital.

It's a beautiful thing

After he started Pianodrome, a piano was brought all the way to Edinburgh from the city of Plymouth in south-west England and appeared unusable.

“All the keys were stuck together because it got a bit damp,” he said.

“I just filed the edges off the lead weights with a mask on so I didn't poison myself. And then when the keys could move, we discovered that it sounded really nice.

The centre holds open sessions where enthusiasts can try out the pianos. When they find one they like, they can "adopt it". Photo: AFP

“I started to be a bit more careful about it and got all the notes working – it ended up being our sort of concert piano.”

Pianos that cannot be restored are pulled apart and turned into sculptures, furniture or art.

One of Vincent-Smith's artworks, a six-metre elephant tusk structure outside Pianodrome's base, aims to highlight what society considers to be waste.

There are also regular events where the derelict shop is transformed into a concert hall in an amphitheatre built entirely from upcycled pianos.

Open sessions where enthusiasts can try out the pianos are also a common occurrence. When they find one they like, they can “adopt” it and take it home in return for an optional small donation.

As the sound of the strings of the concert piano reverberate through the old shop, Vincent-Smith raises his head and nods once – the piano is repairable.

“A piano is just an example of something that our society considers to be waste but can be used to great purpose,” he said.

“So I guess what I'd like to say is to folk, if you're thinking of getting rid of your piano, think about keeping it, it's a beautiful thing, a piano.”

Source: The national news

0 Comments