Fujiwara no Michinaga: Powerful Statesman and Emotional Diarist

The Path to Advancement

The powerful statesman Fujiwara no Michinaga is associated with the poem celebrating his political triumph, written in 1018, while he was in his early fifties: Kono yo o ba / wagayo to zo omou / mochizuki no / kaketaru koto mo / nashi to omoeba (This world / belongs to me— / lacking in / nothing like the / full moon). Many readers view the poem in a negative light, interpreting the pride Michinaga expresses in his power as hubris.

The Fujiwara clan constructed a system whereby its members took effective control of the Japanese state by marrying its daughters to successive emperors and acting as regents. Michinaga reigned at the zenith of Fujiwara power. However, the fame of the above poem has led to a skewed impression of the man. Kuramoto Kazuhiro, a professor at the International Research Center for Japanese Studies who has written several books about Michinaga, argues that “Michinaga had a complex, multifaceted personality, and cannot be discussed solely in terms of his ‘full moon poem.’”

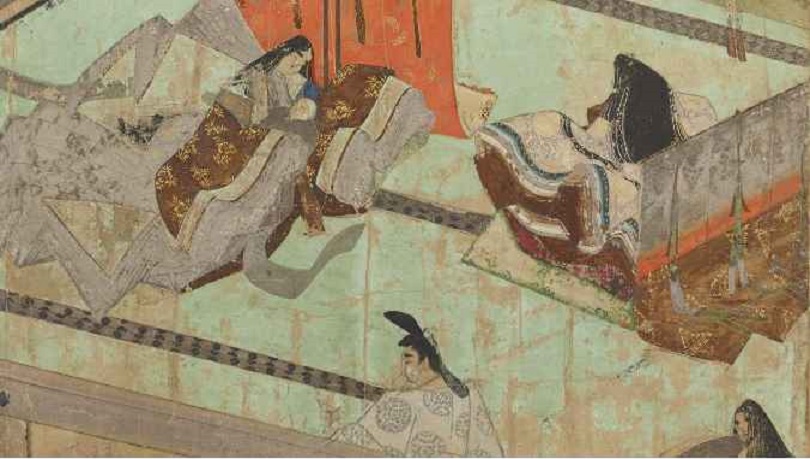

Fujiwara Michinaga in the picture scroll Murasaki Shikibu monogatari emaki (Tale of Murasaki Shikibu Picture Scroll). (Courtesy National Diet Library)

What sort of man was Michinaga, then?

Fujiwara no Kamatari, founder of the clan, had the Fujiwara name bestowed on him by Emperor Tenji in 669 after the two had joined forces to secure power. Kamatari’s son Fuhito had four sons, who each headed branch families, the most prosperous of which was the Hokke, or northern branch.

Michinaga was born into the Hokke branch in 966, the son of Fujiwara no Kaneie. He had four brothers and three sisters. As the youngest of the five sons, he was often overlooked as a child.

Michinaga’s father Kaneie from the nineteenth-century biographical collection Zenken kojitsu. (Courtesy National Diet Library)

Of his four older brothers, only Michitaka and Michikane, who shared the same mother as Michinaga, were eligible to serve as regent. They both were ahead in the line of succession, but died a few months apart in 995. With their passing, Michinaga suddenly found his path to advancement open. He was appointed examiner of imperial documents and minister of the right, and soon was promoted to minister of the left, a lofty post for someone as young as Michinaga.

His nephews Korechika and Takaie, the sons of Michitaka, were political rivals. However, both were exiled following an incident involving an attack on the former emperor Kazan.

Michinaga’s political rival Fujiwara no Korechika (on horseback) in Ishiyamadera engi (Legends of Ishiyamadera). (Courtesy the National Diet Library)

Michinaga’s older sister Senshi was a consort of Emperor En’yū, and her son went on to become Emperor Ichijō. Michinaga and Senshi are said to have been close, something that Kuramoto suggests assisted in his rise.

Unprecedented Imperial Connections

Michinaga paid little mind to his official position, instead focusing most of his efforts on creating ever closer ties between the Fujiwara family and Japan’s emperors. His older sister Chōshi was a consort of Emperor Reizei. Their son became Emperor Sanjō, with Michinaga’s younger sister Suishi becoming his consort.

Michinaga’s daughter Shōshi became the wife of Emperor Ichijō, giving birth to two future emperors, Go-Ichijō and Go-Suzaku. Another daughter, Kenshi, became Emperor Sanjō’s wife, and a third called Ishi in turn married Emperor Go-Ichijō.

To have three daughters marry emperors was unprecedented. Michinaga was firmly at the center of these machinations, and it was around this time that he wrote the “full moon poem.”

An Emotional Diarist

What do we know of Michinaga’s personality? His diary Midōkanpakuki is included in the UNESCO Memory of the World register as the world’s oldest diary in the author’s handwriting. Kuramoto sees this document as holding the secret to knowing the real Michinaga: “It is full of expressions of his emotions—he regularly cries and gets angry, is sometimes fainthearted, and he also grumbles or expresses self-loathing. I think it is common for powerful people to be quick-tempered, but he also writes that he is a fool, revealing a frank-speaking personality, and this aspect may have charmed others.”

Michinaga often cried about his daughter Shōshi, although the tears were not from sadness but from gratitude that she had served her emperor and produced a son who would maintain Michinaga’s power into the next generation.

Kuramoto writes, “Some statesmen feign tears, but I believe Michinaga wept naturally, when overcome with emotion.”

He also regularly sang his own praises. He was known to gather people together for impromptu drinking parties where he would brag about himself incessantly. Sometimes during these sessions, he would reach a kind of ecstasy, believing that whoever he was talking with thoroughly enjoyed his boasting.

There was a darker side to this arrogance as well, as Kuramoto notes: “Among Michinaga’s attendants was a man called Fujiwara no Yukinari, who Michinaga often targeted his anger at. He would yell at him to his face. Michinaga may have been the kind to abuse his power on those around him.”

Fujiwara no Yukinari, who was often a target for Michinaga’s venting. From Shōzōshū 10 (Portrait Collection 10). (Courtesy the National Diet Library)

At the same time, Michinaga displayed a timid side. Once when asked by a temple to write its name for a plaque, he showed an apparent lack of confidence in his abilities. “Michinaga had a weak constitution,” says Kuramoto. “There seem to have been days when he felt unwell, and it is likely that this is when his more timorous nature emerged.”

Yet, he was also high-handed when he wanted to be. He had the ability to force through a situation whereby his daughters were all married to emperors, knowing that this was how he could hold on to power. He had a strong competitive streak too, and this helped him control public sentiment.

As Kuramoto writes, “Both timid and bold, sensitive but broad-minded, sometimes tolerant and sometimes explosively angry, Michinaga as a person is a topic of endless interest.” The “full moon poem” I opened with is an emotional outpouring from a man who did not conceal his nature. It is an honest expression of power.

(Originally published in Japanese on December 25, 2023. Banner image: Fragment from Murasaki Shikibu nikki emaki [Murasaki Shikibu Diary Picture Scroll]. Michinaga’s wife Rinshi [top left] holds her daughter Shōshi’s son, the future Emperor Go-Ichijō. Shōshi is at top right, Michinaga in the center at the bottom, and Murasaki Shikibu at bottom right. Courtesy ColBase.)

Source: Nippon

0 Comments