‘Drive My Car’ is a Modern Japanese Masterpiece

Hamaguchi Ryūsuke’s Drive My Car takes a unique approach to filmmaking to tell a powerful story of loss and hope. The film won four awards at the 2021 Cannes Film Festival and is now in the running for Oscars in four categories. Film studies professor Miura Tetsuya examines the director’s approach and highlights some of the elements that have made his work so appealing to audiences and critics around the world.

What explains the remarkable global success of Hamaguchi Ryūsuke’s Drive My Car? The 2021 film took four prizes at the Cannes Film Festival, including best screenplay—the first Japanese film ever to win this award. This was followed by further accolades at the Golden Globes and the US-based National Society of Film Critics, culminating in the announcement on February 8 that the film had been nominated for four Academy Awards. It is now in the running to become the first Japanese film ever to win the Oscar for best picture. This rush of global acclaim has taken many people by surprise.

In this article, I want to look at the fictional worlds Hamaguchi depicts in his previous work and consider some of the factors I think lie behind the success of Drive My Car.

Inspired by a Classic Western

Perhaps the main reason why Hamaguchi’s work has been so well received by cinephiles, critics, and fellow filmmakers around the world is the ambitious approach he brings to his filmmaking, even while respecting film history and the work of previous generations of directors.

Before starting a new project, Hamaguchi says he likes to return to Rio Bravo, the 1959 Western classic directed by Howard Hawks. Rio Bravo is a carefully crafted masterpiece, where every detail is there for a reason. Of course, Drive My Car does not copy the Hawks film directly. But, for example, in scenes where the film’s protagonist Kafuku Yūsuke (played by actor Nishijima Hidetoshi) and Watari Misaki (Miura Tōko), the young woman working as his driver, talk about their traumatic past, the director is careful to avoid any hint of melodrama or sentimentality. Complex emotions are expressed, or implied, by simple actions. In one scene, Kafuku casually tosses a lighter to Watari. She catches it cleanly and lights her cigarette. It is a simple moment but one that packs an emotional punch. Scenes like this recall the spare, sophisticated atmosphere of the classic Western.

Hamaguchi has absorbed lessons in attention-to-detail filmmaking from past masters. Hawks is only one example of many. Among Japanese directors, Hamaguchi has clearly drawn widely from the work of predecessors like Ozu Yasujirō, Mizoguchi Kenji, Naruse Mikio, Masumura Yasuzō, Sōmai Shinji, and Kurosawa Kiyoshi, who taught him at Tokyo University of the Arts. No doubt the influence of his predecessors is part of what film fans around the world have detected in Hamaguchi’s work. He has studied the history of cinematic expression, and is aiming to build on the past by taking the artform a step forward in a new direction. This makes him an ambitious auteur and stylist of a kind that has become rare in recent years.

The Secrets of a Good Performance

Hamaguchi’s films are also entertaining and refreshing. There is none of the stilted, airless quality that can sometimes mar self-consciously ambitious work. This was particularly true of his other 2021 film Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy, which was imbued with a light, almost poppy sensibility. The idea that Hamaguchi’s films are inspired by a close study of cinematic expression should not give the impression that they are tediously didactic or marked by the kind of introspective solipsism that might limit their appeal to hardcore cinephiles. In fact, Hamaguchi’s films have a wide, almost universal, appeal.

One factor for this, I think, lies in his artistic decision to highlight a fundamental question in his work. Indeed, it has become one of the immovable pillars of his filmmaking: “What makes a good performance?” This is a question of burning interest to anyone. Almost every day, we watch people performing in movies and on television. Sometimes these performances can be quite moving; at other times, they are too stylized and obvious to appear convincing. So, what is the secret to a good performance? Can it succeed in capturing the uniqueness of human life and expressing the complex emotions that can hardly be put into words? And if so, how? Hamaguchi’s films prompt us to consider these basic questions about the artform, and this is at least part of what makes his work so universally appealing.

Filmmakers cannot bluff when it comes to performance quality, as audiences are quick to detect any fakery. However well armed a film may be with theory and ideas, it will fall flat if the performances captured on camera lack conviction. Hamaguchi’s work is the result of a continual process of trial and error, carried out in an unforgiving context, and this is what makes his films so thrilling.

Capturing True Emotions

Hamaguchi dates his ambition to become a filmmaker to his encounter with one film in particular: Husbands (1970) by John Cassavetes. The film is not especially well known in Japan, where it never received a cinema theater release and has never been released on DVD or other media. Cassavetes was critical of mainstream Hollywood movies for smoothing out the inherent complexity of human reality and presenting it as something flat and, for him, uninteresting. Alongside his work as an actor, he gathered a group of friends who shared his ambition to make a different kind of film. This group worked on their own project on weekends and at nights. The result was a new approach and a totally fresh type of film. Audiences found the shocking novelty of his films difficult to warm to and Cassavetes never found commercial success as a director, but his work resonated with a coterie of passionate fans.

Inspired by Cassavetes, a major interest for Hamaguchi since the beginning of his career has been the question of how to extract convincing depictions of emotion from actors. His career to date has been dedicated to finding methods that will allow him to achieve the kind of performance he wants. The early fruits of this quest can be seen in films like Passion (2008), Shinmitsusa (Intimacies, 2012), and Happy Hour (2015). The last of these was set in Kobe, and took nearly two years to make, based around a long-term workshop whose participants had no previous acting experience. The finished film has a running time of 5 hours and 14 minutes. Hamaguchi has said that he made Happy Hour as a female companion piece to Husbands, and for a while the film had the working title of Brides.

Drive My Car also asks what a performance is and how it is possible to capture the constant churn of complex emotions going on inside any human being. The result is considerable depth, far removed from the flatness and simplicity that Cassavetes criticized. At the same time, the film sets out to examine difficult questions from a position of equality and openness with the audience. Hamaguchi does not put on airs or indulge in obscurantism. He trusts his viewers, and invites them to ponder the questions together. In this sense, the film is remarkably “audience-friendly.”

In the film, Nishijima Hidetoshi plays a theater director Kafuku Yūsuke, who himself is obsessed by the question of what it means to give a performance. The approach to acting and the kinds of performance that Kafuku tries to coax from his actors in the film represent the same kind of artistic search on which Hamaguchi was embarked in Happy Hour and other films. The director boldly shares with audiences the journey that he and his actors are on and the questions they are hoping to answer through the process of making the film.

Diversity and Filmmaking

Perhaps another reason why Drive My Car has received such international acclaim has to do with the contemporary mood and the move to embrace the value of diversity. What can film do as an artform to combat the tide of exclusionism and chauvinism around the world? In the second half of Drive My Car, actors from different backgrounds come together to rehearse and perform a theatrical production of a Chekhov play, each speaking in his or her own native language. One woman uses sign language. It is not hard to imagine how this element of the story, which unambiguously looks to draw power and strength from diversity, might have appealed to critics in today’s climate.

The film does indeed recognize the value of diversity—but this does not come simply from its presentation of a multilingual drama as part of the narrative. The drama only works because it is built on painstaking groundwork through which the director has trained himself to communicate with actors from different linguistic backgrounds and understand how they express themselves through their voices and bodies. This is something that required Hamaguchi to reshape his approach to performance and direction on a deep level. He has said that to make Drive My Car, including the drama segment, it was necessary to carry out a fundamental rethink of the system used to produce the film in cooperation with the producer and his co-directors—in particular with regard to the way of allocating time (and at times battling against the traditions of Japanese filmmaking).

As a result, the film goes beyond having diversity as one of its themes to show that filmmaking can itself be diverse and varied (particularly with regard to the collaboration between director and actors). If Drive My Car embraces diversity, it does so on a profound level. I suspect that this is what has most impressed and surprised filmmakers and critics around the world. It shows that performance and production can themselves be a source of diversity. In Drive My Car, Hamaguchi demonstrates that a new approach to the production process makes it possible to create a different type of film.

Destruction and Recovery

Why has an auteur like Hamaguchi emerged in Japan at this time? I would like to close this article by considering a few of the possible reasons, including the director’s background. Hamaguchi was born in 1978. By the time he graduated from university and was ready to embark on a professional career, the boom years were over and Japan’s economy had entered its ongoing period of chronic sluggishness. People of Hamaguchi’s generation have lived through two major earthquakes and witnessed the collapse of the promise of security and increasing prosperity that previous generations took for granted.

Another important factor is the trilogy of documentary films Hamaguchi made in Tōhoku in the years following the March 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake: Nami no oto (The Sound of the Waves, 2012), Nami no koe (Voices from the Waves, 2013), and Utau hito (Storytellers, 2013). It was in this series of harrowing documentaries that Hamaguchi took the subject of destruction and recovery and made it his own. As part of the process of recovering from the destruction of their everyday reality, people sometimes take a fresh look at the world around them and find hints of new possibilities. For several years, Hamaguchi has used his work to depict this kind of contemporary hope. Drive My Car marks the latest point of arrival in this journey—for now.

As Hamaguchi himself has repeatedly emphasized, much of the power of Drive My Car comes from Murakami Haruki’s original stories, with their focus on regrets and solace and recovery from emotional trauma—while mainly based on the story of the same name, it takes elements from other works. But the resonance with Hamaguchi’s own experiences in the devastated areas of Tōhoku and the story’s echoes of the questions that have haunted him are also part of what makes the film such a successful screen adaptation. After a traumatic event has come to an end, how do we go on living, and what should we hope for? These are the vital questions Hamaguchi probes in his work. No doubt they have struck audiences particularly powerfully now, as the suspension of normal everyday life drags on in the shadow of the coronavirus pandemic.

Drive My Car is not just an outstanding example of filmmaking. It also succeeds in capturing and expressing something profound about the contemporary moment. For this reason, it is likely to be remembered for a long time.

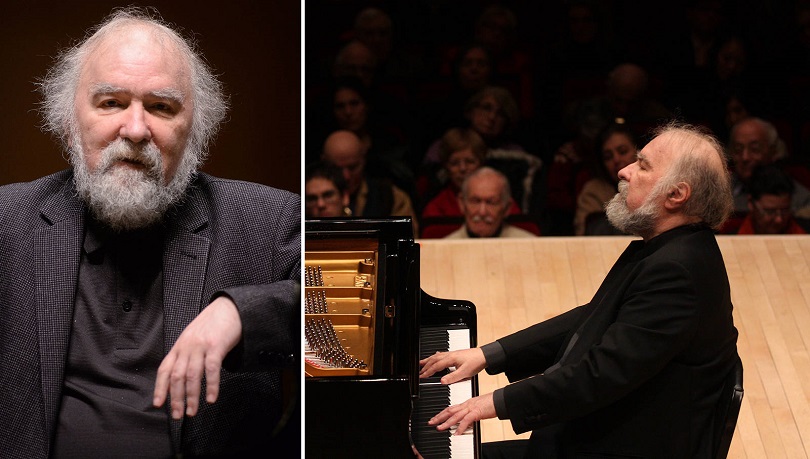

(Originally published in Japanese on February 24, 2022. Banner photo: Actors Nishijima Hidetoshi (left) and Miura Tōko. © 2021 Drive My Car production committee.)

0 Comments